Origami and Orientalism

by Marcus

Part One: Something That Totally Won’t Be Controversial At All

Paper airplanes are pretty cool.

That’s probably not how you expected me to start this essay; just try to stick with me for a bit. I must have folded hundreds of paper airplanes throughout my elementary school years. They took a backseat once I started pursuing other forms of paperfolding, but recently, I inexplicably got back into them. Of the paper airplane books I own, only two feature models folded from single uncut squares: Origami Aircraft by Jayson Merrill, and How to Make Origami Airplanes that Fly by Gery Hsu. It was this second one that drew my interest, as well as my concern – not for any of the designs, but rather the text in the introduction, an excerpt from which is provided below:

“Pure origami is an ancient and elegant art; making paper airplane is a pastime of relatively recent origin. Origami is concerned with beauty whereas paper-airplane folders usually place a premium on performance. In addition, origamians tend to follow strict conventions while paper-airplane folders may create their own rules as long as they have fun.”

Huh. One is tied to deep, ancient traditions while the other is new and innovative. One is concerned only with appearance while the other cares about practicality. One is bound up by strict rules, but the other can defy rules and have fun. Now where have I heard these sorts of things before? Because – and here’s the actual controversial bit – these don’t sound like descriptions of origami so much as stereotypes of Japanese people.

The essay that follows is truly global in scope, jumping from the Italian Renaissance to the World Exhibition in Paris to a swimming pool in St. Louis. It follows centuries of little-known origami history in order to challenge commonly held misconceptions. It further unpacks those misconceptions to expose within origami a narrative founded on racism and colonialism that still remains largely unchallenged. There’s no model this time – this isn’t a “companion essay.” This is a larger project than any one model, or any set of models. It is a project whose reach is larger than origami itself.

Welcome, one and all, to Origami and Orientalism.

Part 2: A Crash Course in Inventing History

Through my conversations with people over the years, I often find a set of preconceived notions people have about origami. Some common ones: origami is a centuries-old Japanese art, passed down through the years, done with specialized origami paper, consisting of a small, fixed set of simple models, and of course, strictly forbidding glue, scissors, and rectangles. These comprise what I call “The Ancient Japanese Art of Paperfolding.” I should clarify that this applies specifically to origami as art – the recent proliferation of origami in technology (spacecraft, car airbags, medicine, etc.) is more widely recognized. Yet while origami is seen as radical and innovative when applied to technology, these words are rarely used to describe folding for its own sake.

The study of origami history is frustratingly sparse. Paper, the medium of origami, is intransient. Even those who explicitly study the history of paper tend to focus on more important things than folding. There are many gaps in the origami historical record that will likely never be filled. Yet there is a growing body of work dedicated to origami history, such as Dave Mitchell’s Public Paperfolding History Project, and it provides an important counter to this narrative. The Ancient Japanese Art of Paperfolding, it turns out, is largely unsubstantiated, and inconsistent in many places with the historical record. In this section, we will turn to history to develop a more accurate picture of what origami is.

Our first exposure to folding tends to be in kindergarten or elementary school. This is the domain of the fortune-teller, the jumping frog, the many, many paper airplanes. To an extent, this is the result not of the Japanese, but rather the 19th century German educator Friedrich Froebel, the founder of kindergarten. Froebel promoted the use of paperfolding to demonstrate simple geometric relationships to children, like the fact that two joined isosceles right triangles form a square (easily demonstrated by folding a square in half diagonally). Later educators in the Froebelian tradition developed a more complex system of folded patterns. Froebelian folding was taught in kindergartens in Europe, the United States, and – plot twist – Japan, where they intermingled with the existing folding tradition. In fact, Japanese folder Koshiro Hatori has traced several supposedly Japanese models to the influential kindergarten system in Japan, such as the waterbomb, piano, and fortune-teller. (It will be a recurring theme throughout this essay that much allegedly Japanese origami is in fact influenced by Western nations.) These are often some of the first models people ever learn, and it would do us well to understand where they really come from.

Wealthier readers of this blog may be familiar with another type of folding, one that doesn’t even involve paper in the first place. Folded cloth napkins are a common table decoration at upscale restaurants and have a shockingly long history, dating all the way back to the Renaissance. The Trattato delle piegature, an Italian text on napkin folding, was first published in 1629, and the art is presumably even older than that. Napkin folding is influential in ways one might not expect: in the Trattato delle piegature, a variety of animal forms are depicted, as well as abstract patterns of pleats that seem to foreshadow modern folders like Chris Palmer or Paul Jackson. Some research even traces the origami terms “mountain fold” and “valley fold” to early napkin folding manuals. It’s another important example of folding in Europe that’s rarely ever considered when talking about origami. Even though napkins are not paper, and a great length of time has passed since its heyday, napkin folding still provides a precedent for the origami of today.

Let us now return to Japan to discuss yet another type of folding. The Kan no Mado is a 19th-century Japanese text with instructions for 48 different paper designs. The pictured models display a charming, simple elegance – perhaps the closest example so far to what Gery Hsu was picturing – but they would never be considered origami by modern standards. Cuts are everywhere. Irregularly shaped paper is everywhere. Models like a dancing monkey, a dragonfly, a spider, and more are made from cut squares, stars, and hexagons. Here, an internal contradiction in The Ancient Japanese Art of Paperfolding emerges: old Japanese origami and pure, no-cuts origami are clearly not the same thing! The birth of origami purism would in fact only happen many years later, with the development of modern origami.

Indeed, as fascinating as these historic examples of folding are, modern origami outweighs all of them in complexity, artistic depth, and sheer scale. For one, modern origami heavily uses three-dimensional shaping techniques, popularized in the second half of the 20th century. Complex shaping is often impossible with so-called “origami paper,” and multiple kinds of specialized paper have been developed by folders to allow for it. Neal Elias and Max Hulme, two prominent folders in the 1970s, used malleable foil paper to make their designs. Akira Yoshizawa developed the technique of wet-folding, using the size (a class of water-soluble adhesives) in wet paper to create soft curves that harden when the paper dries. Papers suitable for wet-folding are often handmade, obscure, and not marketed as “origami paper,” limiting their recognition to only especially dedicated folders. Nonetheless, Yoshizawa’s work (comprising an estimated 50,000 models) is widely considered the birth of modern origami, and his shaping method has been updated and expanded by folders ever since. The hard angles and flat surfaces omnipresent in classical origami have given way to volume, life, and real artistic expression.

Just as important to modern origami is the modern revolution in mathematical design technique. Box pleating, a system of grid-based folding, was pioneered by the aforementioned Elias and Hulme, leading them to create some of the first human figures and manmade objects in origami history. Circle packing (and later, tree theory) is a set of design algorithms simultaneously discovered by Robert Lang and Toshiyuki Meguro in the 1980s; with it came arthropods, deer with full antlers, and more designs of astounding complexity. It is, in fact, these developments that led to the rise of “pure origami”: it was not until the modern era that most things could be made from folded paper without cutting and glue. Instead of purism constraining the development of origami, the rise of mathematical design proved that anything could be accomplished without cutting or gluing. The result has been an explosion of modern origami designs, still going today, surpassing everything before it by several orders of magnitude. Quite far indeed from the image we typically have of a centuries-old Japanese dogma!

So with the knowledge of all these different kinds of folding throughout history, how can origami possibly be reduced to The Ancient Japanese Art of Paperfolding? If the designs in the Kan no Mado require so much cutting to produce points and layers, how can we call it folding? If folding existed in the Italian Renaissance, and so many traditional models originate from Europe, how can we call it Japanese? And if the vast majority of the technique and artistry in origami has only been possible for less than a century, how can we call it ancient? These six words fail to capture so much of origami, and their existence does an incredible disservice to the art form. Many folders, such as Robert Lang and Michael LaFosse, acknowledge its falsity. They stress that origami is new, that much of it is non-Japanese, and that “origami paper” is unsuitable for much folded art. What they miss, however, is why these misconceptions are so popular, and the social and political forces that keep them in place. To understand this piece of the puzzle, we will turn to arguably the most famous origami model of all time: the Flapping Bird.

Part 3: It’s a Bird! It’s a Crane!

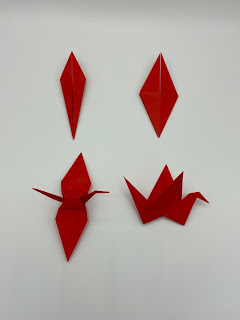

We must first distinguish between the flapping bird and the orizuru, or the paper crane. The two are often confused, both being stylized bird models folded from the Bird Base. But there is a critical difference between them: an extra step in the crane narrows the head and tail flaps, locking them in place. The flapping bird omits this step, and thus its wings flap when the tail is pulled.

This small change gives the two models very different functions. The crane is a symbol of life and death; it has ties to the Shinto religion, samurai culture, and the bombings of Hiroshima and Nagasaki. The flapping bird, on the other hand, is a playground toy, an amusement for children. Perhaps the most important difference, though, is this: the flapping bird isn’t actually Japanese.

Let’s back up for a moment. In the Western world, modern folding has three main precedents. The first is the napkin folding exemplified by the Trattato del piegature. The second is the folding tied to Froebel and the kindergarten system. The third is that of stage magic: folding used not as art or as education, but instead purely for amusement. This third lineage is exemplified by folded constructions like the Troublewit or the book Paper Magic, written by none other than Harry Houdini. And it deserves our special attention, for it is where we find the first mentions of the flapping bird. An 1885 article in the French popular science magazine La Nature contains the first instructions for the flapping bird, attributing it to les prestidigitateurs japonais–the Japanese conjurors, common at magic shows in Europe and America. Later writings by Gershon Legman, an early American folder, reinforce this connection between the flapping bird and magic.

Why is this significant? Stage magic, in fact, has a long association with Orientalism: magic has long been a way of drawing a barrier between the supposedly simple, primitive East and the supposedly advanced, modern West. Stage magicians often dressed in exoticized “Asian” clothing and performed allegedly Asian magic tricks: consider the infamous example of William Robinson, who performed in yellowface, pretended not to speak English, and went by the stage name Ching Ling Foo. World fairs and exhibitions, organized and hosted by Europeans, showed off the fantastical and mythical elements of Asian cultures, like magic (Indian mathematics or Chinese astronomy, for example, were curiously absent from these exhibitions). Each of these served to project a distorted image of Asia, tailored to the desires of the colonial powers of Europe and America, and only barely resembling the real Asia at all.

In fact, while the flapping bird has well-documented links with Japanese magicians that performed in the West, strangely little comes out of Japan proper. The American folder Robert Brokop once took a trip to Japan and asked every origami master he met where the flapping bird came from; none were able to answer. David Lister, the famed British origami historian, noted that while any Japanese person will recognize the orizuru, one can “show that same Japanese the Flapping Bird and he or she will express delight and surprise and say that he or she has never seen it before.” The oldest concrete evidence that the Japanese even knew it existed is from 1957, in a photo of Gershon Legman teaching it to a group of Japanese children. Many writers on the history of the flapping bird – Gershon Legman, Dave Mitchell, and David Lister among them – seem to conflate the Japanese conjurors with Japan, and are confused by the flapping bird’s connection with the former but not the latter. The obvious answer is that les prestidigitateurs japonais never represented Japan in the first place. The flapping bird was a product of the imperial West, born from attempts to strip Asia of its power and create shallow imitations of its culture. It is Orientalism distilled into a single object.

It is no exaggeration to say that the rise of the flapping bird was the birth of origami. Not the birth of paperfolding, but the birth of the idea that paperfolding was Japanese, and the Orientalism that came with that idea. The La Nature article was republished in other countries within a matter of years. The “Japanese” design spread to America, Spain, the United Kingdom, and beyond. More importantly, it spread an Orientalist legacy that still remains tied to origami. Look at the proliferation of origami paper with machine-printed, quasi-Japanese flower patterns – never mind that real chiyogami and yuzenare handmade and aren’t meant to be folded in the first place. The ban on paper cutting is reinvented as an ancient Japanese tradition, more “proof” that Japanese people want nothing more than to obey strict, unchanging rules. And of course, any notion of modernism in origami has been lost on the public, because it is critical to Orientalism that the West is seen as new and innovative, and the East as old and traditionalist. All the developments of Yoshizawa, Elias, Hulme, Lang, Meguro, Peter Engel, Brian Chan, Satoshi Kamiya, Michael LaFosse, Richard Alexander, Fumiaki Kawahata, John Montroll, Eric Joisel, Jun Maekawa, Issei Yoshino, John Szinger, Shuki Kato, Giang Dinh, Isao Honda, Quentin Trollip, Hojyo Takashi, Manuel Sirgo Alvarez, David Brill, Paul Jackson, Seiji Nishikawa, Kade Chan, Kota Imai, Chen Xiao, Shuzo Fujimoto, Jason Ku, Yoo Tae Yong, Gen Hagiwara, Fukui Hisao, Hideo Komatsu, Ronald Koh, Joel Cooper, Kyohei Katsuta, and so many others? They are made completely irrelevant by this framing. All of modern origami artistry is erased by Orientalism.

Part 4: The Emotional Emptiness of Origami (or, Why That’s Not Actually True)

I first conceived of the idea for Origami and Orientalism while working on my previous essay, Everything is Awesome. I deliberately glossed over the reasons why origami wasn’t that impactful, hoping to devote this essay to that part of the story. But in writing Origami and Orientalism, I’ve done a lot more research into origami, and I’ve gained a much different perspective on origami as a result. This section’s going to be a response to Everything is Awesome; if you haven’t read that one, you can honestly just skip to part 5.

When I say, “origami hasn’t moved me a lot, emotionally,” that’s not really true. There are plenty of origami works that stand out. Eric Joisel’s musicians sparkle with a uniquely French playfulness and life. Tomoko Fuse is best known for her modular polyhedra, but she has a series of larger pieces that play with shape and light in mesmerizing ways. Erik and Martin Demaine’s curved sculptures feel like truly modern art, hard to understand but impossible to stop trying to understand. And of course, Akira Yoshizawa’s vast oeuvre demonstrates his complete command of expressions and a deep respect for the medium of folded paper.

Now, a commonality exists between these four examples: most have never had written instructions. (Origami models without instructions are, incidentally, an entirely modern phenomenon, with the emergence of models too complex to be diagrammed.) Perhaps that makes sense. Art, almost by definition, cannot be replicated, and anything that can loses artistic value. When I bemoaned the lack of emotional content in origami, I largely restricted my view of origami to things other people designed and I had folded–which all had instructions! Of course I was never going to derive much meaning from them. I could combine them, arrange them in different ways, like I did with the four Dragon Kings, and I was adding my own meaning to those models in doing so. But merely copying instructions is not art.

Throughout the history of social hierarchies, there have always been members of oppressed groups that stood against their own class interests. There have been women that have opposed women’s suffrage, Black people that have argued for segregation, and Asians that have reinforced Orientalism. I’m ashamed to say I’ve been part of that last category. In Everything is Awesome, I mischaracterized origami, ignoring much of the work that modern origami artists have done, and perpetuated Orientalist views of it in doing so. I still hold to the other half of my conclusion – that on my blog, I need to prioritize quality over quantity – but I’m not making origami artistic in doing so. It already was.

Part 5: The Curious Case of the Missouri Swimming Pool

In 1919, Fairground Park in Saint Louis opened what was then the largest swimming pool in the United States. This being Jim Crow era-Missouri, the pool was only open to White people. But after civil rights leaders argued for the pool to be integrated (and did so successfully), attendance plummeted, and the pool was eventually drained and closed down. The pool could have been a public resource shared by all, but white city authorities chose instead to destroy it entirely. Racism, in its refusal to let Black people make gains in society, ended up being a loss for White people as well.

I feel like something similar applies to origami. When I show people pictures of things I’ve folded, one of the most common questions I get is, “Do you design all of these yourself?” To most of my peers, I am the only origami artist. The mind clouded by Orientalism places all creativity in origami onto one individual. It never occurs to people that origami has a community, because nobody can imagine a community based around a non-art. The crumpled organic forms of Vincent Floderer, the masks of Eric Joisel, the hyper-realistic insects and animals of Satoshi Kamiya – these are indisputable proof that it is art. But so many people (White or otherwise) have never seen them. Racism, in its refusal to value Asian culture, ends up being a loss for White people as well.

Origami has brought me incredible joy for more than a decade of my life. It has made me an better artist and a better scientist. It has connected me to people from Asia and Europe and the Americas. I know origami folders to be people who readily collaborate and always share new ideas with their fellow folders, entirely devoid of selfishness. It is, in short, a community I am eternally grateful to be a part of. My greatest regret is that too few people are truly part of this community, and in asking why this is the case, Orientalism has emerged from the proverbial shadows and revealed itself as the answer. A world without Orientalism is thus a place where complex, artistic origami is accessible to all. It is a world where everyone wins.

Part 6: Towards an Anti-Orientalist Origami

There’s no model associated with the essay, because I don’t have any models that add anything to it. Like I said in Everything is Awesome, every essay I write changes the way I think about origami. I’m still adjusting to this way of thinking about it, as inherently tied to the politics of Orientalism. Eventually, I think I’ll produce origami that is anti-Orientalist in nature. But it is something that will come with time and effort. It will come with discussion: antiracism is done by coalitions, by groups of people. As far as I know, nobody else has written anything like this essay. I had to synthesize a lot of disparate, unrelated works by different people in order to make it. For the time being, I walk this path alone.

It must also be recognized that origami is far from the only thing affected by Orientalism. Consider the recent appropriation of Indian religious practices by New Age practitioners, or the recent appropriation of congee by the Breakfast Cure company. Origami happens to be the thing I can speak to; I don’t have “the solution” to Orientalism. I’ll readily point you towards other resources (Ibram X. Kendi’s How to Be an Antiracist is an excellent primer on antiracist strategy, and Cathy Park Hong’s Minor Feelings is a great work from an Asian American perspective), but I am far from an expert on the subject. I would like to propose one thing, though. “The ancient Japanese art of paperfolding” was a story created by, and for, White people. So what would an Asian story of folding look like?

For starters, it would be incredibly diverse. Folding has exploded in popularity across Asia, branching far beyond Japan; Chinese folders like Xiaoxian Huang and Vietnamese folders like Nguyễn Hùng Cường have recently found international success alongside their Japanese and American peers. It would, of course, be modern, acknowledging the mathematical and artistic developments of recent generations of folders. I also imagine it would be a form of cultural expression in and of itself. Many Asian cultures have indigenous papermaking traditions. Japanese washi is probably the most well-known, but there’s also Korean hanji, Nepalese lokta, and Vietnamese giấy dó, all of which are used in origami already. Many of these are endangered, unable to compete with cheap, machine-made, Western-style paper. Folding can be a way to advocate for these papers, a point of Asian cultural pride instead of a weapon of imperialism. Strengthening this narrative and laying The Ancient Japanese Art of Paperfolding to rest is one step towards an anti-Orientalist origami. There is much more to do (and I welcome any suggestions) but correcting myths about origami is an easy first step that basically anyone can do.

I have seen origami used as a symbol for activism (by Tsuru for Solidarity), a usage of the art I wholeheartedly support. Activism for origami is much less common. Perhaps origami is considered too obscure, too insignificant a subject for antiracists to devote time to. But there is no “insignificant” racism. As Martin Luther King Jr. once said, injustice anywhere is a threat to justice everywhere. Racist thought in one part of our life, no matter how small, will always be able to spread to a bigger part of our life. To anyone who loves folding as I do, and to anyone who finds racism and imperialism detestable, the time has come to rid origami of Orientalism.

Sources

(annotations where appropriate)

Part 1:

Hsu, Gery. “How to Make Origami Airplanes that Fly.” Dover Publications, Inc., New York City, NY, 1992.

I should mention that Gery Hsu is far from a prolific folder; this one book contains his only published origami. The book is, if nothing else, a good example of the Orientalist ideas about origami entrenched in the public consciousness.

Merrill, Jayson. “Origami Aircraft.” Dover Publications, Inc., New York City, NY, 2006.

By far the better of the two paper airplane books. The diagrams are more comprehensive (though still far from perfect), and the planes fly better and encompass a wider range of shapes. Despite this diversity, there are enough similarities between the airplanes that the enterprising folder can begin to fold their own airplanes in his style. Merrill also runs an active YouTube channel, where he posts video tutorials of new planes.

Part 2:

Mitchell, David. “Froebelian Paperfolding and the Kindergarten.” The Public Paperfolding History Project, http://www.origamiheaven.com/froebel.htm.

The Public Paperfolding History Project is an invaluable resource when it comes to the history of early paperfolding. Documents from Japan, Spain, Germany, and more trace the development of folding both practical and recreational. This was an eye-opener when it came to non-Japanese folding, of which there is an impressive amount, and the page on the Flapping Bird was in fact the direct inspiration for this essay.

Lang, Robert J. “Origami Design Secrets,” 2nd edition. CRC Press, Boca Raton, FL, 2012.

The definitive text on technical origami design (albeit essentially by default, there really are no other ones). The modernity of origami is a point that Lang explicitly clarifies early on, and is a theme repeated throughout the text. Also contains some interesting insights into Renaissance-era napkin folding, acknowledging a small amount of continuity between it and modern box-pleated designs.

Mitchell, David. “The Kan no Mado.” The Public Paperfolding History Project, http://www.origamiheaven.com/kanomado.htm.

Lang, Robert. “Paper.” Robert J. Lang Origami, August 9, 2011, https://langorigami.com/article/paper/

A short primer on paper usage in origami, written by Robert Lang himself. Introduces pretty much everything (kami, foil paper, wet-folding, and so on) concisely and with a good sense of humor.

Part 3:

Mitchell, David. “The Flapping Bird.” The Public Paperfolding History Project, http://www.origamiheaven.com/historyoftheflappingbird.htm

Goto-Jones, Christopher. “Magic, Modernity, and Orientalism: Conjuring representations of Asia.” Modern Asian Studies, Volume 48, no. 6, 1451-1476. Cambridge University Press, 2014. JSTOR, http://www.jstor.org/stable/24494638

One more thing that didn’t quite fit into the essay: William Robinson’s stage name of Ching Ling Foo was a direct appropriation of the name of a real Chinese magician, Chung Ling Soo. The entire story of the conflict between the two would actually be pretty hilarious if it weren’t so blatantly racist.

Lister, David. “Origins of the Flapping Bird.” The Lister List, British Origami, https://www.britishorigami.org/cp-lister-list/origins-of-the-flapping-bird/.

The Lister List is a collection of the writings of David Lister, the renowned British origami historian. Unlike Mitchell’s project, the Lister List is not a timeline, but rather a collection of topics Lister found interesting and wrote about in the British Origami Society’s mailing list. The collection is quite impressive and is worth taking a look at in future essays, but this particular page was the only one that found its way into Origami and Orientalism.

Mitchell, David. “The Flapping Bird.” The Public Paperfolding History Project, http://www.origamiheaven.com/historyoftheflappingbird.htm.

LaFosse, Michael G, and Richard Alexander. “Advanced Origami.” Tuttle Publishing, 364 Innovation Drive, North Clarendon, VT, 2005.

A more in-depth guide to origami paper selection than Lang’s article, as one might expect from the creators of the Origamido Studio. Discusses different types of fibers and their utility for different subjects, and even contains tips on how to make your own custom origami paper. Also reaffirms the newness of origami, both technically and artistically (one of the many ways this book forms a weird connection with Origami Design Secrets). Informed the comment about Chiyogami prints not being used for actual folding.

Part 4:

Ho, Marcus. “Everything is Awesome (or, The Emotional Emptiness of Origami).” Origami by Marcus II (blog), 2022, https://foldbetweenthelines.blogspot.com/2022/06/everything-is-awesome-or-emotional.html

Yes, that is my own essay. Looking back, I wrote it somewhat hastily, and I certainly could have done more research before declaring “origami is all boring and showy.” I guess I was referring to things on my own blog (which is probably a reflection on my own skill level more than anything). Oh well. I try to make up for it here.

Joisel, Eric. “Musicians.” Eric Joisel | Le Magicien du Papier, http://www.ericjoisel.fr/en/musicians-2/

Eric Joisel needs no introduction. I could have used any one of his compositions to illustrate my point, but I think the dwarven musicians form the most cohesive set out of his many works.

Fuse, Tomoko, Hideto Fuse, et al. “Tomoko Fuse’s Origami Art.” Tuttle Publishing, 364 Innovation Drive, North Clarendon, VT, 2020.

I’m not a huge fan of modular origami, and until I started researching this essay, I didn’t have the impression that Tomoko Fuse was a particularly good folder. This rather surprising find utterly shattered that impression. Fuse’s large-scale works are geometry at its most beautiful, worthy of a place alongside Leonardo da Vinci and MC Escher. There are instructions for select models, but even they are extremely minimalistic, leaving the actual arranging of the elements (and the lighting, another significant part of her work) up to the reader. Her more mainstream books, meant to be simple and repeatable, display only the tiniest fraction of her artistic power.

Demaine, Erik, and Martin Demaine. “Curved-Crease Sculpture.” https://erikdemaine.org/curved/

Some of the weirdest origami I’ve ever seen, and that’s meant in the best way possible. Demaine and Demaine (a father-son duo) are some of the premier mathematicians in the folding world, and they rarely venture into pure art. Still, their sculptures always stick out to me as completely unique artistic statements. Their use of curved folds, often considered to be outside the realm of mathematical folding, makes for highly un-origamistic origami that is, to my knowledge, unreplicated by anyone else. Go check them out.

Lang, Robert J. “Design Challenge at OrigamiUSA.” Robert J. Lang Origami, September 29, 2015, https://langorigami.com/article/design-challenge-at-origamiusa/

Part 5:

Blake, John. “A drained swimming pool shows how racism harms White people, too.” CNN. Last updated March 6, 2021. https://www.cnn.com/2021/03/05/us/heather-mcghee-racism-white-people-blake/index.html

Part 6:

Vishali. “There’s Nothing New About The New-Age.” Medium, An Injustice!, May 7, 2020. https://aninjusticemag.com/theres-nothing-new-about-the-new-age-45274e51a62f.

Breen, Kerry. “Breakfast Cure brand sells ‘improved’ congee, sparks controversy." Today, July 19, 2021. https://www.today.com/food/breakfast-cure-brand-sells-improved-congee-sparks-controversy-t225951

Xiaoxian Huang’s Flickr page: https://www.flickr.com/people/huangxiaoxian/

Nguyễn Hùng Cường’s Flickr page: https://www.flickr.com/photos/blackscorpion/

Tsuru for Solidarity, https://tsuruforsolidarity.org/

An organization dedicated to closing migrant concentration camps in the United States, descended from the Japanese American interment reparations movement. The origami portion is largely symbolic, but it’s still a nice touch.

This comment has been removed by the author.

ReplyDelete