Okay, the title's a bit of a misnomer; I have not folded every insect ever designed by Robert J. Lang. That would include things like the box-pleated Stag Beetle, the Yellow Jacket, and Snack Time. But I have folded the entirety of Origami Insects and their Kin and Origami Insects II, his two published books of insect and arthropod models. Furthermore, I have folded them all from three-inch tissue paper. Yes, really.

I don't approve of virtuosity for virtuosity's sake, as I've explained previously in Everything is Awesome. Origami should be about more than showing off. But I feel this is different for two reasons. First, this isn't really a grand display of virtuosity. If you want to see one of those, Lang's own renditions should suffice. I make plenty of interpretive mistakes, leaving some flaps too thin and showing too many layers in others. I've struggled with these, and the finished models reflect the struggle that went into them. I feel that's kind of a good thing.

Furthermore, I do have something to say about the project. I'd like to offer some analysis of the two books, the models contained within, and some observations about Lang's evolving design style over the years. I'm also including some advice on the technical problems of the models, for anyone curious enough to fold them. (If you do, please be sensible and use larger paper than I did.)

Part 1: Origami Insects and their Kin

This early book, published in 1995, contains twenty different insects and other arthropods. The design language is still not fully developed, relying heavily on conventional 22.5° structures and point-splitting as opposed to his later insects. Still, one can find hints of Lang's future development as an insect creator scattered throughout. The models are highly diverse, despite their older design idiom, and several are serviceable as études in specific folding techniques.

Pictures are shown for each, atop a U.S. quarter for comparison.

Treehopper

The most manageable of the book (and the largest from a fixed sheet size); the only truly difficult step is the releasing of a hidden edge in steps 32-33. Constructed from a modified Stretched Bird Base.

Spotted Ladybug

Already much more difficult than the preceding model. The spotted elytra introduce two new challenges: the folding of small, hard-to reach details of the spots themselves, and the hard-to-fold middle points used for the legs. Appropriate paper choice is difficult, demanding a thin, duo-colored paper. Painting a black sheet red on one side may be a workable strategy.

Orb Weaver

Lang's trend of using octagonal structures for spider models, continued in the second Tarantula, is present here. Steps 21 and 22 may pose a challenge to the novice folder; they are best performed as one step.

Tarantula

More difficult than the Orb Weaver, even as they appear similar. Folded from a similar base to the Treehopper and Ant.

Tick

Comes in two variants, the Hungry Tick (white) and the Sated Tick (red). Simpler than most other models in the book.

Ant

Contains an unusual locking structure in the middle segment of the body. Jeremy Shafer's concept of "creep" is relevant if this part of the model is to be folded successfully. Two variants also exist for this model, albeit in a less significant way (the antennae can also be jaws).

Butterfly

Lang himself has taken a negative view of this model over time, considering it "misshapen, clunky, and lifeless" in Origami Design Secrets. I would be inclined to slightly disagree. The Butterfly is not misshapen so much as it is hard to interpret cleanly. Inelegant steps abound in this model, from the sinks and Elias-stretches in steps 28-31 to the unsink folds in steps 43-52 that produce the legs. The antennae are made from asymmetric points, and will appear to be slightly different lengths if folded imprecisely. Multiple attempts, however, can remedy these issues, and a particularly thin paper such as the Hikaritori tissue used here gives the wings an alluring translucent quality. This is still not enough to fully redeem the model; it is long and difficult, and repays little of the effort put into it.

Scarab Beetle

Possesses the typical "bug" shape, made slightly more interesting by duo-colored paper. The mechanism that locks the antennae flaps to the head is clever, though its effectiveness will be reduced if the chosen paper is too thin (like Hikaritori tissue, for example).

Cicada

The eyes have a slightly cartoonish charm, and the wings have a similar effect to those of the Butterfly. Otherwise, Lang's second version in Origami Insects II is superior for realism.

Grasshopper

The oldest model in the book, constructed from a point-split Bird Base. Well detailed despite a simplistic structure. Some small closed sinks may present an issue.

Black Pine Sawyer

Foreshadows some of the developments of Origami Insects II, such as the gaps between legs and the shaping of the body (the latter reminiscent of the Acrocinus longimanus). Overall not difficult; some closed sinks can be modified for simplifying purposes.

Dragonfly

The wings, like those of the Butterfly, are difficult to fold cleanly, though repeated practice will solve this problem. The eyes and legs invite comparison with Montroll's insects.

Hercules Beetle

Gains a direct revision in Origami Insects II, although the model in this book is perhaps the one that needs revision the least. A wide variety of poses are possible, giving much room to the imaginative interpreter.

Long-Necked Seed Bug

The design on the abdomen, representing the overlapping wings of the bug, prefigures the Cockroach of Origami Insects II. Two closed sinks in step 92 are the hardest part of the model.

Pill Bug

This model, owing to its three-dimensionality, is the most reliant on foil or wet-folding. The model's main weakness is the construction of the legs, which all emanate from a single point; the model is also quite small relative to the starting sheet.

Praying Mantis

The hardest part of the model is in steps 36-57, where the central middle point is split into antennae; the earlier and later steps are much less difficult. Similar to the Orb Weaver, it is recommended that steps 41 and 47 be performed as one step to obtain a cleaner result (taking care to do this on the right layers). The profile of the model is distinctive and not difficult to shape.

Stag Beetle

A long, convoluted sequence of landmark folds at the beginning will test the folder's precision. The rest consists of standard 22.5° angled structures, with some sink folds. The shaping given in the instructions results in a somewhat boxy model; further interpretive choices are therefore required.

Paper Wasp

Arguably the finest of the models in this book. The profile is recognizable and highly accurate, and small details are numerous upon closer inspection. Step 66, a double crimp/sink combo, is likely the hardest single step in the book; extreme precision and control (and a willingness to start over!) are necessary.

Samurai Helmet Beetle

The model remains two-dimensional until a surprising and ingenious sequence at the end, which elevates and rounds out the body. The main difficulty of the model is the small, hidden sink fold sequence in steps 76-80. The main branched horn is rather short, a problem remedied in the more anatomically precise Origami Insects II version of the beetle.

Scorpion

A reliance on 22.5° structures renders all the legs equally long, an issue Lang corrects in (say it with me now) the updated version in Origami Insects II. Unorthodox unsink folds in steps 31 and 82 pose a technical problem, for which there is no real solution beyond "being patient."

Part 2: Origami Insects II

Published a mere eight years after the previous book, Lang's second set of origami arthropods already shows a much greater command of the form. Technically, the book is much more advanced than the first, demanding skill with sink folds, irregular landmarks, wraparound folds, and thick layers of paper. Frequent color changes are a notable feature as well.

The models are also much harder to interpret, demanding more detailed and sensitive shaping skills than those in the previous book. The naturalist approach taken in this book requires a strict and precise, yet lifelike, interpretation. Of special usefulness here are the designer's own renditions, photographed and shown at the beginning. Satisfactory folding of the models will be infeasible without consulting these.

(Models shown with a quarter again, just zoomed in more.)

Butterfly

Possesses no legs, in an attempt to make this model simpler and more elegant than the oft-maligned butterfly from the first book. It largely succeeds in this regard; nevertheless, the thickness of the layers in steps 19-20 still makes it slightly cumbersome.

Acrocinus longimanus

Created from a heavily modified Frog Base, the model incorporates a large number of sink folds and thus demands thin paper. The model, while repetitive, is technically simpler than other models later in the book.

Ant

The first of Lang's more irregular, circle-packed designs. The shaping of the body into its three segments is done in a single step, and takes special care. The aforementioned pictures in the beginning provide a more complete idea of how to achieve the correct shape.

Tarantula

A sort of "too-good-to-be-true" model, squeezing eight legs, two pedipalps, a head and an abdomen into a very tight space. Arranging the flaps cleanly, particularly the two thick middle points that form the pedipalps, is the main interpretive difficulty. The paper needs to fulfill the paradoxical requirements of being thick and soft (to achieve the right texture for a tarantula) but also thin and crisp (to keep up with the technical demands).

Pill Bug

The evenly spaced legs are achieved by a unique parallelogram-based structure, challenging to precrease and collapse. Like the Pill Bug from the first book, the outer shell is highly dependent on foil or wet-folding. Some unusual crimps in step 81 are another challenge. A great improvement from the first Pill Bug, in both simplicity and accuracy.

Cockroach

Technically and structurally similar to the Ant, minus the segmentation. Beware of the "make sure the edge falls about 2° short of the crease" step!

Dragonfly

If the first Dragonfly was more Montroll-like, the second is distinctly Lang: the eyes are gone, and the legs are positioned in the front, as they are on the real insect. This second is more accurate, although the first one arguably has more character.

Eupatorus gracilicornis

One of the few insects in the book with a full set of wings. A difficult, yet surprisingly origamistic, model; all the angles are placed at multiples of 11.25°, making it more manageable than its spiky appearance would suggest. The crease pattern is perhaps the most stunning one in the whole book.

Scorpion

A triumph of mathematical design, constructed with Lang's TreeMaker program. The legs are spaced out with rivers and increase in length from front to back (as they are in real scorpions). The numerous, seemingly arbitrary landmarks are the major point of difficulty; the rest of the model, while tedious, is easier than it appears.

Flying Ladybird Beetle

Contains the first of three steps marked "This is hard," specifically a closed wraparound. It may be helpful to invert the flap by pulling the layers out from the inside, rather than wrapping the outer layers around. A point of curiosity: a truly accurate model requires three-colored paper (body, spots, and wings).

Longhorn Beetle

An obvious precursor to Lang's later box-pleated models seen in Origami Design Secrets and beyond. Folders with experience collapsing crease patterns are encouraged to skip steps 1-27 and simply precrease the given crease pattern. Folders without such experience are also encouraged to do so as an introduction to the technique.

Praying Mantis

"The three words that best describe you are as follows, and I quote: sink, sank, sunk!" The technical demands of the model are obvious at first glance; the thin body and legs require good layer management and exceptionally thin paper. (While Lang says as much at the beginning of the book, I do not think he imagined that the paper used would also be three inches to a side...)

Periodical Cicada

Structurally simple (aside from another "This is hard" step in the wings) but detailed and highly evocative. Requires subtlety in shaping.

Flying Cicada

Constructed from a similar base to the Flying Ladybird Beetle, and roughly tied with the former as the hardest model in the book. Like the first Butterfly, complex sinks and unsinks pose a great difficulty; folding the wings cleanly is one of the more subtle challenges.

Flying Grasshopper

An elegant crease pattern belies a rather awkward precrease, where certain folds must fall slightly short of a given landmark. Much like the Tarantula, a large number of points crowded into a small space makes a clean interpretation difficult (further compounded with duo-colored paper).

Samurai Helmet Beetle

Arguably the greatest of all of Lang's insects. Uses box-pleating maneuvers (again foreshadowing designs in Origami Design Secrets), but the model as a whole mixes structures and forms in a Kamiya-esque manner, defying simple categorizations of "box-pleated" or "circle-packed." Captures the three-dimensionality of the subject better than any other model.

Hercules Beetle

A direct revision of the Hercules Beetle from Origami Insects and their Kin. Lang's evolution in shaping proficiency is most clearly evident in the difference between the two models. Less room for interpretation, but greater detail and a more realistic shape are positive features.

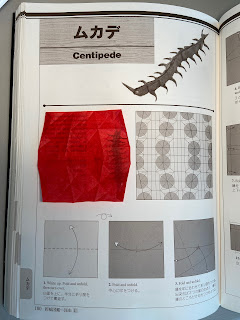

Centipede

Structurally similar to the Pill Bug, albeit in an even more complex form. Demands thin paper, extreme patience, and proficiency with frankly appalling reference points.

Part 3: Conclusion

The history of these models provides a key insight into Lang's evolution as an origami designer. The earliest models are derived from well-established bases, such as the Bird Base, even as they are heavily modified. In certain models, however, the shortcomings of these bases are made clear. Lang makes a breakthrough with the development of circle packing (and tree theory, really just an extension of circle packing), allowing the creation of custom-made structures for any arbitrary model. Many new designs, including redesigns of old subjects, are made possible.

The price of Lang's new circle-packed designs is, of course, irregularity: creases run at odd angles and pass through hard-to-find reference points. A sort of dialectic emerges here, with classical regularity on one side and precise mathematical design on another. Lang quickly finds a synthesis of the two, seen in models like the Tarantula. While the model relies on irregular angles, it does so within the confines of an octagonal geometry, greatly simplifying the model without compromising on features. A similar thing happens with the Longhorn Beetle: while some of the points could have been made more efficient, the simplicity and regularity of the crease pattern make this design hard to improve on.

All this experimentation will bring Lang's insect design process to its full maturity, with the development of polygon packing. Though it does not appear in full force in this book, it is the basis for virtually all of his later insect models. The Yellow Jacket, Stag Beetle, Snack Time, and countless others are full of fantastic shaping, anatomical precision, and extreme technical difficulty. The drive for naturalism, prominent throughout these two books, reaches its peak in Lang's polygon-packed insect models.

Many of these points correspond to the chapters of Lang's book Origami Design Secrets. Indeed, in that book, Lang takes us through the evolving processes of origami design, moving through grafting, tiling, circle packing, and tree theory, and uses many of his own insects as examples. These two books, then, are more than just origami books. They are a window into an artist's life, his quest to isolate that most elusive of artistic subjects – the insect – and the endlessly enjoyable, finger-twisting results of that quest.

This has been a fun (and tiring) project, and I hope you've gained something from it like I did. If you made it all the way to the end, congratulations! Here's a bonus model for you.

BONUS MODEL: Silverfish

Superficially similar to the Stag Beetle, in the long sequence of landmarks followed by mostly conventional 22.5° structures. In every other way, it is a tremendous improvement. The model captures the exoskeletal segments well, along with the forked tail. Shaping is not difficult at all if one simply follows the instructions. On the other hand, the many sink folds (all condensed into a single step) are sure to test the patience of even the most proficient folders.

Sources

Lang, Robert J. "Origami Insects and their Kin." Dover Publications, New York, 1995.

Lang, Robert J. "Origami Insects II." Origami House, Tokyo, Japan, 2003.

Lang, Robert J. "Origami Design Secrets," 2nd edition. CRC Press, Boca Raton, FL, 2012.

Chronological listings of the models (with opus numbers, an idea Lang takes from classical music) are available here, here, and here.

Comments

Post a Comment